GM Toolkit - Central Place Theory

Sometimes something hits your brain like a pile of bricks. I lurk on mastodon far more often than I ought to, but this post actually paid dividends.

Now, thanks to ACOUP I was already familiar with the idea of cities needing hinterlands (and those being often omitted in modern media), but I was struggling to understand how to arrange those cities on, say, a hex map.

Enter central place theory, a theory on the distribution of cities. After watching some YouTube videos to get my head around the idea, here’s how I was able to use it.

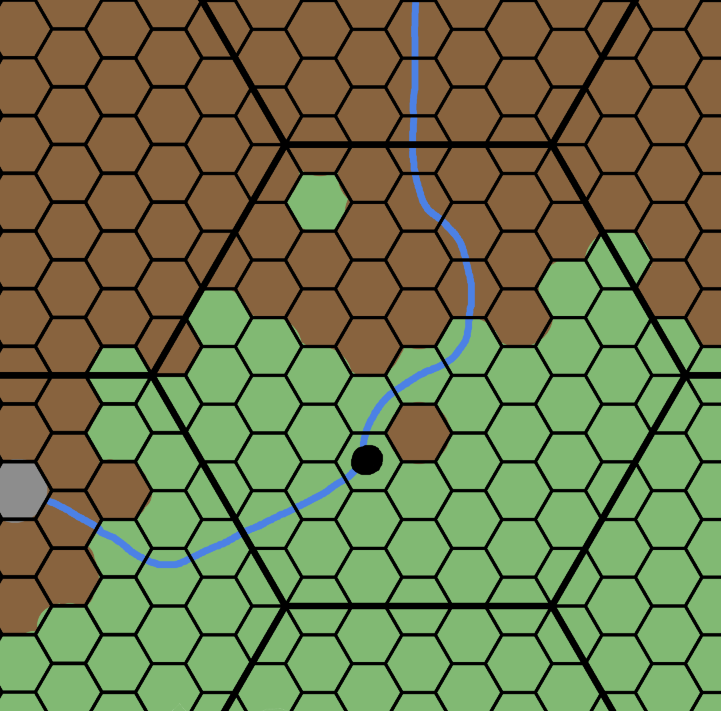

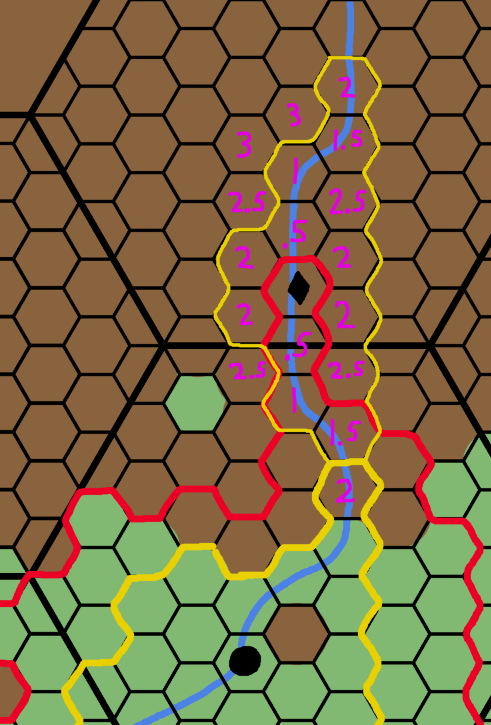

My starting point was already having geography in place, as well as the location of the largest city I wanted. I already had some loose modifiers for travel time in mind. These are 3-mile hexes so entering a flat hex takes one hour at walking speed. So I made hills take 2 and rivers take 0.5. These probably aren’t the travel time I’ll use in play for players but they’re simple enough demonstration purposes, and it isn’t yet clear to me whether they need to match up exactly or not.

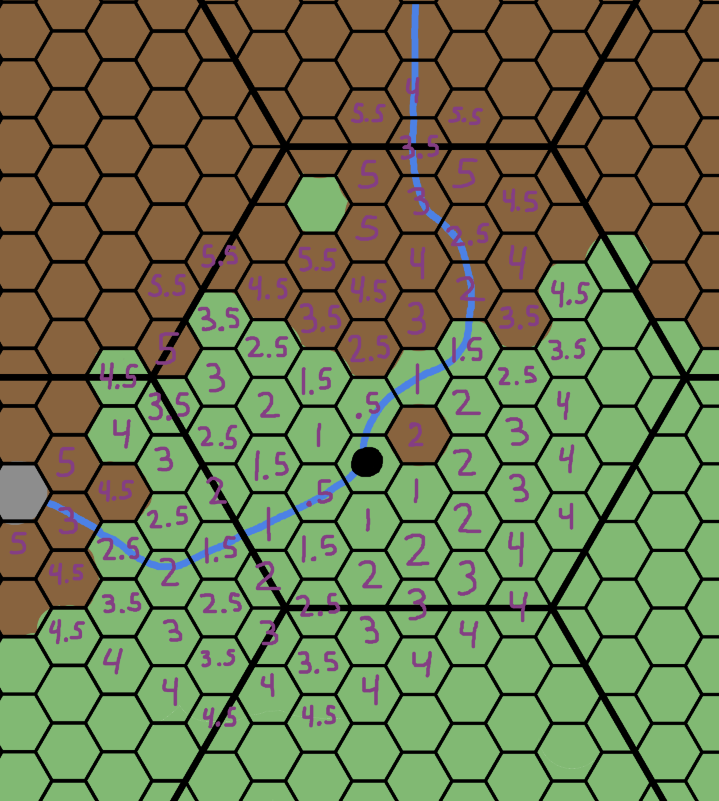

Now, we start by finding the travel time to each hex from the main city. We start by finding the distance to each hex adjacent to the city, then find the distance to each hex with the lowest distance, and continue until we’ve filled the area. This is a simple pathfinding algorithm and isn’t too tedious to do by hand (though this example quickly got bigger than I expected). For this example I’m not tracking the distance more than four hours for reasons I’ll explain shortly.

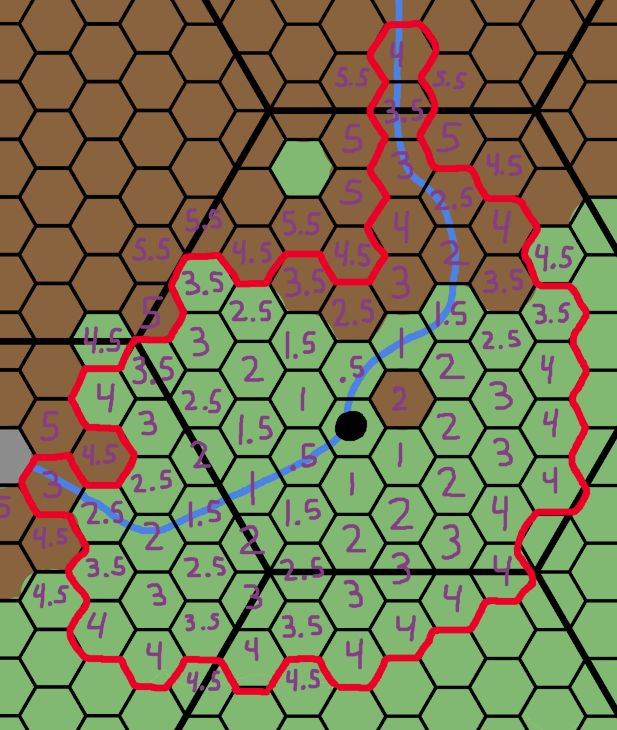

Now I’m going to draw an outline containing all the hexes which are four or less from the center city. What this represents, according to the central place theory, is all the hexes containing settlements which will go to the main city for whatever things they cannot get in a more local market. I’m also using it to define a border between settled and “wild” lands – a dubious concept but one which the fantasy of the OSR is usually built on.

According to our theory, the main city also contains all the services of a smaller level town as well. If we assume that the reach of a smaller settlement is two hexes, we can draw a second outline inside the first to represent all those settlements which will also go to the main city to get less rare goods.

So far this is pretty uninspiring. But the real magic happens when we consider the following. All the settlements between these two outlines also need a market for local goods. Or another way to look at it is for each given service it takes a certain amount of settlements within a certain range to be able to exist, so if a region can support these services they will crop up. Some, usually more specialized, services require more people to be profitable, so they are scattered sparsely, whereas more common services require less people so they’re scattered more densely.

We can prevent overlap by placing these towns twice their reach from one another. We’ve already calculated distances from our city, so we can start putting towns on hexes that are four hours from the city.

So I’ve placed a town up north and calculated the borders of its reach.

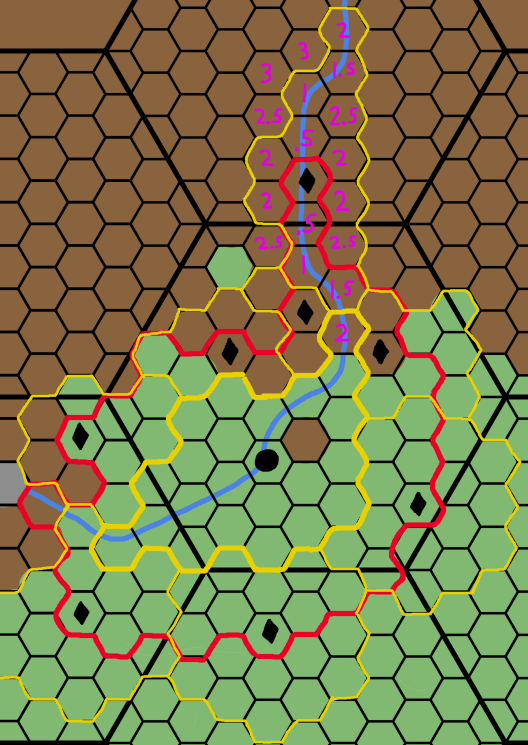

Now, central place theory says that regions of the same level shouldn’t overlap, which is something I failed to do for this map. Four hours was actually a miscalculation not accounting for the quantized nature of the hexes. It should have been five hours, and in general twice the distance plus one hour should produce results with no overlap. There’s also going to be artefacts due to the way I’m calculating distance not being the same in both directions (I’m only counting the cost for “entering” a hex and ignoring the type of hex I’m leaving. This is what I do during games) and the fact that unlike the central place theory I’m not putting smaller settlements on smaller grids.

In any case the next step is to repeat this process until all the settlements inside the outer outline of the main city are served by towns.

In case it isn’t clear, I want to point out that I’m assuming every “empty” hex inside these boundaries contains a village. I just didn’t want to draw them in.

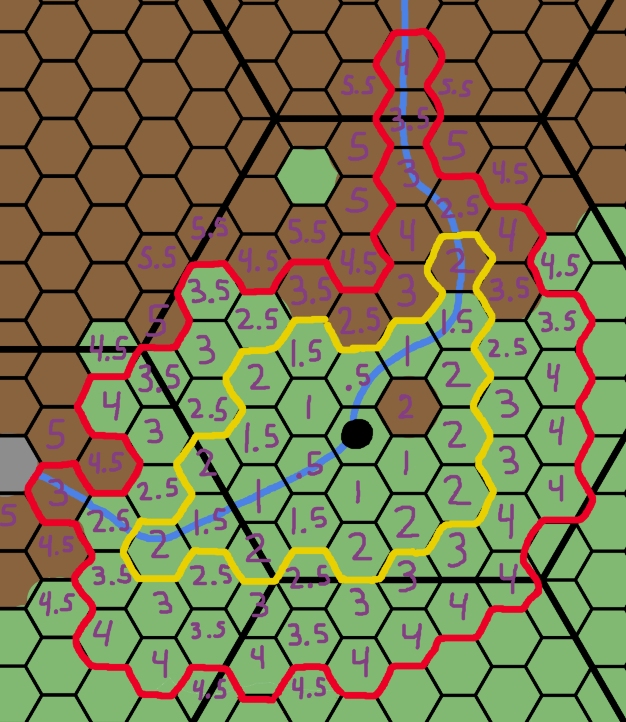

Again you’ll see more overlap than the theory predicts in the ideal case. That’s; it’s close enough for our purposes. But you’ll also notice that I’ve extended the outline of these towns outside the red outline for the city’s market. This stems from central place theory assuming all land evenly contains settlements and not allowing for borderlands. This is an example of what settlements might look like in a “points of light” setting – hand-placed cities with smaller towns and villages scattered a short distance around them.

This leaves the question of what to do with these “empty” hexes still within the. I’ve elected to put settlements in them, deciding that they’re smaller due to their more limited access to the city’s markets, creating a new level on the settlement hierarchy below our basic settlement. We can call these hamlets as opposed to the baseline settlement of villages. I’m tempted to speculate as to what a more realistic solution might be, but it would be fairly baseless. These artifacts can be left in to create a bigger variety of region sizes, as I could see things getting a little too simple on a flat plain.

So it might be fair to say that this technique is really more inspired by central place theory than truly based on it. It’s close enough for my purposes of having a process deciding the placement of settlements smaller than cities.

But the main takeaways of central place theory are directly useful:

- Settlements contain the goods and services of all the settlements further down the hierarchy

- Settlements of the same size are roughly evenly spaced by travel time, which gets smaller as you go down the settlement hierarchy.

Wait, why bother randomizing where the settlements are?

I have a lot to say on how procedural generation can be used in ttrpgs, but for now the reason I’m using proc gen is because this system works as an oracle. It’s no different than a random encounter table or, for that matter, a game system. It’s a way for a GM to generate outcomes via some internal logic that is independent of them, which allows them to encode ideas they wouldn’t necessarily think of themselves when simply improvising off the cuff. It’s just in the prep phase rather than the running phase of the game for the GM.

Additional Ideas

Instead of assigning two levels of services – town and city, we could assign three and see where things end up. Services with a range of 4, 3, and 2, for example. I’m not sure how this will affect our ability for settlements to contain the services of all settlements below them, but that ought to hold for the reason that having to go to two different places for two different services is a pain in the ass and that would cause the services to move.

This system could be used for distributions of things other than cities, such as magical sites in the world.

These market area borders could also be used as somewhat natural political borders, because they are based on travel times. With geography and artifacts distorting the regular grid shown in central place theory they’re irregular enough I don’t think players would notice unless it was pointed out or your campaign is taking place on an infinite plain. And there’s nothing stopping you from adjusting political borders after the fact as you see fit. The overlaps could be used as conflict regions where feudal lords are butting heads.

Even if not used for political borders you could have a go at using these areas as markets for item prices, though that would require computer aid very quickly. I’m still looking for better ways to handle simulating markets.

Speaking of computers, there’s also the temptation to set this up as a computer algorithm, either on a hex grid or operating on the pixels in an arbitrary image using shaders.

Bonus

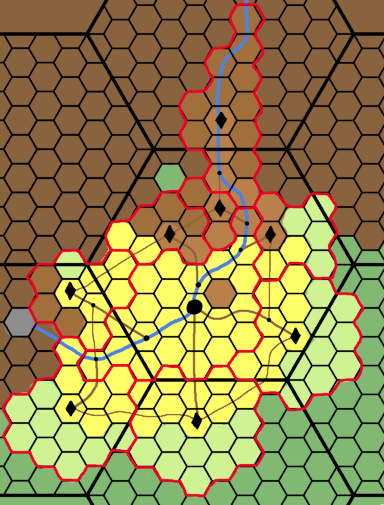

My example map, cleaned up and colored to indicate market borders (I like to use yellow to represent fields), with a road system added.

2024-07-22

Moss Woods Campaign Review, Part 2

Once more with feeling! This is the second half of my retrospective on my 15-player Moss Woods campaign (Part 1)

What Failed?

If I had to point to any one thing which killed the campaign it would be an excess of ambition. I underestimated the drain and time involved in running sessions twice a week; running one session consistently is hard enough. While I’m more or less proud of the quality of what I prepared for the game, the quantity and rate of production left a lot to be desired. I had a grand vision for the region that I wasn’t able to live up to. I’ve been in this cycle before. It takes me a long time to prep things, leading to improvising more and more of the game, leading to frustration from feeling as though I’m underdelivering, the stress of which makes it harder for me to prep. It’s a personal issue – the players don’t seem to notice or mind. I think the way to avoid this in the future is primarily to prepare material which can be re-used rather than consumed and secondarily to add new material to the game world on my schedule rather than the player’s. Part of me wonders if running the game as a true open table would have helped; because I was running three separate parties I felt pressure to ensure they found stuff in the directions they went. If I had put more explicit walls on their sandbox and let them run amok within those boundaries, I perhaps ironically might have had an easier time expanding them. I think the main benefit of this technique would be keeping a clearer demarcation between the “live” parts of the game world and what isn’t ready yet. Often, things I was working on were “real” to me in the game world even if they weren’t to the players yet, so I would mention them offhand in sessions and players would act on that information, distressing me as I was under-prepared for that eventuality. I’m not above improvising when my back is against the wall, but I enjoy running games much more with the proper level of preparation. While convenient at the table, improvisation has unseen costs afterwards as I need to take notes on what I made up for the future.

Of course there were several other factors contributing to the campaign’s end. Particularly, my advancement system became increasingly problematic as the campaign dragged on. I had adapted Spwack’s X advancement system in order to allow players to develop their own characters. They loved this and it became a hallmark feature of the campaign for them but it quickly became a source of dread for me. I had to restrict spending Xs to only be usable on perks (perks were the equivalent of feats or class abilities) to spare my sanity, especially early on when players were turning to me to come up with what the upgrades were. Even with these changes I found the dynamic uncomfortable as it often felt like my players were trying to extract as much power from me as possible as I tried to curb their power arbitrarily. I often found myself exhausted at the end of a session (already tired from work) being badgered about the precise details of upgrades. Eventually I instituted a policy of players coming to me between sessions with written drafts for their upgrades. Another problem was my tendency to give out powers requiring bespoke mechanics to be developed, sapping my time. High stats caused combat balance issues as attack ability was tied to them directly, so a system was instituted such that stat improvements cost more Xs as they got more powerful. Ultimately I think a fixed three Xs per perk or upgrade is mathematically unsustainable for a campaign of this type. Parties gained Xs as a group and the fixed cost of upgrades meant players who died would never catch up. In terms of time required for inventing perks it also meant the pressure never let up as the characters became more powerful. For future games I plan on keeping player input for perks but tying perk and stat gain to something which provides diminishing returns. That and the policies of players not bothering me about advancement right after sessions and needing to send written drafts ought to keep things more manageable. If the game is large enough I might create some harder guidelines, set up a dedicated discord channel for people to homebrew perks, and deputize players to help manage that. Needless to say I will also be decoupling stats from combat ability, or at least making it harder to achieve excessive stat gain.

My hexcrawling rules proved to be another factor in killing the campaign. Moving from place to place using these procedures sapped valuable session time and didn’t provide much in return. While I’m sure my rules could be tweaked to fix these problems, this campaign has convinced me that exploration and travel should not be using the same procedures. I might do some experiments with this and come back with a more developed post but in short I’m finding traditional hexcrawling rules work exploring for new sites or for low abstraction survival scenarios, but travel between known points can largely be handled as a point crawl instead with the benefit speeding the game along. I’m also thoroughly disillusioned with six-mile hexes and watches as the main unit of time at this point. They’re too much of an awkward middle ground between scales when compared to hexes that take an hour or a day to move across. Going forward I’m going to use three mile hexes for local hexmaps. This will mean travel can be handled in hours instead of watches, which has the knock on effect of making the time to perform pioneering activities such as making canoes, felling trees, or digging holes more meaningful than handling such activities in four hour segments. I’m aware that my frustration with hex crawling might come off as similar to attitudes about travel and random encounters first seen in the 3rd edition crowd (seeing such things as speed bumps to the “real” game), but I’ve been trying to make hexcrawling work for years and it’s time to try something different. I see this as an extension of the idea that characters can move faster through rooms they’ve explored in a dungeon than when they’re exploring new rooms and expect it to provide similar benefits.

What succeeded?

Timekeeping with multiple parties was a concern of mine at the start of the campaign, to the extent I wrote a whole (somewhat incomprehensible) post brainstorming different methods for handling it. I ended up going with the one-to-one time system described there. Even though it technically affected the game, the timekeeping didn’t make a huge impact. Some things were tied to real world time such as the passing of the seasons and moon phases for some types of wizard, but the parties pretty much went off in other directions and managing their comings and goings relative to each other has been trivial. Earlier in the campaign I was much more diligent with timekeeping and parties bumped into each other here and there and passed messages and items. If the parties were interacting more it would be a bigger deal. I’m wondering if it’s possible to switch to a lazier method of tracking time where the events of sessions are just assumed to not overlap and the one-to-one time is only used for world events like holidays, seasons, moon phases, and faction turns. One of the big reasons to have one-to-one time was to be able to bring patrons into the game, but running three parties hasn’t left me with the time I would need to run those extra players. I suspect those games with patrons aren’t running as many sessions per week as I was or had some other method of running them which was less GM intensive. Still, I consider the timekeeping system a success even when handled loosely. That said, I still have at least one player ardently annoyed by the idea of not being able to pick up sessions immediately where they left off. And there have been some times where that would have been convenient. I’ve been able to divine from this post that the BrOSR 1 actually uses a locking mechanism for locations as described in AD&D, so my previous understanding of locking and one-to-one time being separate techniques was faulty (therefore so was my assertion that Gygax clearly didn’t use one-to-one time as the BrOSR insists. I think it’s an open question at this point). It seems that such locking could be further utilized to allow the same party to explore a dungeon more fully. I can’t imagine any way to express this to players in character and I’m not sure that’s necessary; it is a meta constraint after all. One thing which I noticed with nominally one-to-one time was how messed up my own sense of time is with regards to the agricultural year. If players capture a herd of sheep the temptation is to allow the sheep to be sheared regularly, but of course if realistic time is to be used this only happens once a year. Some things like this require longer periods of seasons or even years to pass as downtime. That could be something I tie to my prep cycle – if the foundations are sound instead of ending the campaign when I need a break or time to prepare more material I could gather people’s downtime and go onto hiatus, skipping extra game time during the interim. This allows me to deliver on the promise of plans which stretch over game years without having to commit to running the game for that amount of time and allowing myself breaks in the process.

One to one time ties directly into downtime, which was much more manageable than advancement and extremely rewarding. I do want to keep doing downtime for this style of game as it helps draw player investment, but next time it will need to be mainly self-serve to preserve my sanity. I should be able to hand players the downtime rules and have them declare actions without my input. Or again deputize players to help me manage that aspect of the game.

Mechanical Thoughts

Here are some things I struggled with from a system/campaign design perspective which I want to touch on briefly.

First of all, I struggled to support my magic systems. The last game had three: arcane, divine, and spirit 2. I still like that trifecta for a more classically fantastic game. My main struggle was providing enough mechanical “hooks” into these systems in the game world. An example of needing hooks would be ensuring treasure hoards have spellbooks for casters in a system where they don’t automatically get spells from leveling up. I did an alright job of this for the arcane magic system, and there were a handful of hooks into the divine and spirit magic systems, but the majority of my prep was done before either were in my ruleset. I still want to expand on those systems but will need to ensure there are more altars and spirits about to interact with.

Secondly, I feel like the combat could have been better. The biggest changes from traditional OSR rulesets were making movement in combat zone-based and having a two-action economy. I think both of those changes worked out well enough but need some light refinements I might discuss elsewhere. However, with the zone based movement I was having a hard time making ranged combat feel “right”. Ranged weapons in RPGs tend to bother me by being too short range, but I also don’t want them to totally dominate. I think long ranged combat outside the reach of melee requires its own procedures, which might be as simple as tracking the relative distance between two parties. A penalty for attacks at longer range is required, and I still need to figure out how to model cover and people moving up to melee range while under fire in say, a forest, but I think the bones are there. I’ve found GURPS to have the best ranged combat in RPGs and am taking notes, though I aim for a simpler system. Another concern was making combat more dynamic. A lot of my combats have boiled down to “I hit the guy” on repeat. I had previously thought that having Dark Souls style active defenses such as dodges and parries would be a good way to spice things up and still find that tempting because “I dodge the attack” is something every new RPG player tries. But my explorations of that design space have ended up unsatisfying and I’m instead of the opinion I need to add a stunt roll similar to that seen in this post. I also need to be more deliberate about ensuring that combat itself is tactically interesting alongside mechanical changes, especially when it comes to terrain. A lot of the fights in this campaign happened in vague and undefined woodlands which should have affected fights more and should have had more terrain features.

Finally, an open problem is how best to handle bookkeeping. I’m fully onboard with the OSR maxim of counting torches and tracking items thoroughly, but I consider this a cost which has to be paid for the benefit of interesting logistical decisions. Certain innovations such as inventory slots ease bookkeeping for items immensely, but there must be other ways to speed up this part of the game. Tracking every single little item is a lot of effort for an often dubious reward. I’m of course aware of the idea of overloading encounter rolls to also deplete resources, as seen in Errant and elsewhere, but have never liked that approach as it makes depletion rates inconsistent. I think my players would agree. The two approaches I’m currently considering are increasing the level of abstraction for resources once a certain scale is reached – looking at Ultraviolet Grassland’s sacks of supplies as an example, and looking further into resource dice as seen in the Black Hack. I’ve played Forbidden Lands, which uses a resource dice system that ties the dice to slots. While rolling the dice adds another step to the depletion process, I feel like this is mitigated by the decreased frequency of updating the ledger. Other than those two mechanical ideas, I’m also looking to introduce explicit player roles. Some parties do this naturally but in others it falls entirely on one person, which bothers me. Explicitly demarcating the roles of quartermaster, scribe, and mapper into separate players lightens the load for each and emphasizes the importance of doing these things.

Footnotes

-

Unfortunately they’re the only group I’m seeing actively pioneering this style of play. But nobody said I had to like them to steal their techniques. ↩

-

On the topic of spirit magic, I want to shout out Renaissance Woodsman’s series of posts. There are some things I don’t personally like (it’s a little too all-encompassing for my tastes), but it’s a great example of the sauce spirits can bring to a fantasy setting. ↩